Since moving to Tennessee, we have had the opportunity to visit a number of sites honoring the history and complexity of racial issues that have faced, and continue to face, our country. We have conversed with many people whose families have lived for generations in the South, as well as made our own observations about the city and surrounding areas. This, along with current events, has set a lot of ideas and information swirling in my head.

Racial injustice is not an easy subject to confront, much less address. I tried to talk myself out of writing this post, knowing it would be neither easy nor fun. But, since I strongly believe that this is an area that we need to continue to understand and have conversations about, it would seem a bit hypocritical of me to avoid the topic. While writing a long post on our experience dressing up as Disney characters for a children’s breakfast may have been entertaining, it certainly wasn’t important. This, on the other hand, is an area of vital importance, but it is ugly and difficult.

My experiences these past few months have allowed me to better appreciate the depth of some of these issues. Though of mixed-race myself, growing up in a middle-class Seattle suburb and attending a modern, big-city university had somewhat sheltered me from racial issues and prejudice. Upon reflection, I think I unconsciously viewed slavery and the civil rights movement in the 60s as discrete eras and naively attributed modern-day issues to a select group of racist or intolerant individuals. Yes, I was aware of the disproportional crime rates amongst African Americans, as well as increased use of police brutality against that group. But I think I failed to see, or didn’t bother to look at, how our nation’s dark past has so deeply ingrained itself in the cultural beliefs and legal systems that continue to perpetuate these injustices.

I am not an expert on these issues, so please do not confuse me for such. The following is merely my attempt to organize my thoughts from several recent experiences. This is not an orderly history lesson on civil rights issues. I will try to focus on points that I felt particularly moved by, found surprising, or thought worth reiterating. I hope that reading this spurs you to learn more (even if only while fact-checking me) as well as reflect more on your own experiences and how we might confront some of these issues in our communities and country.

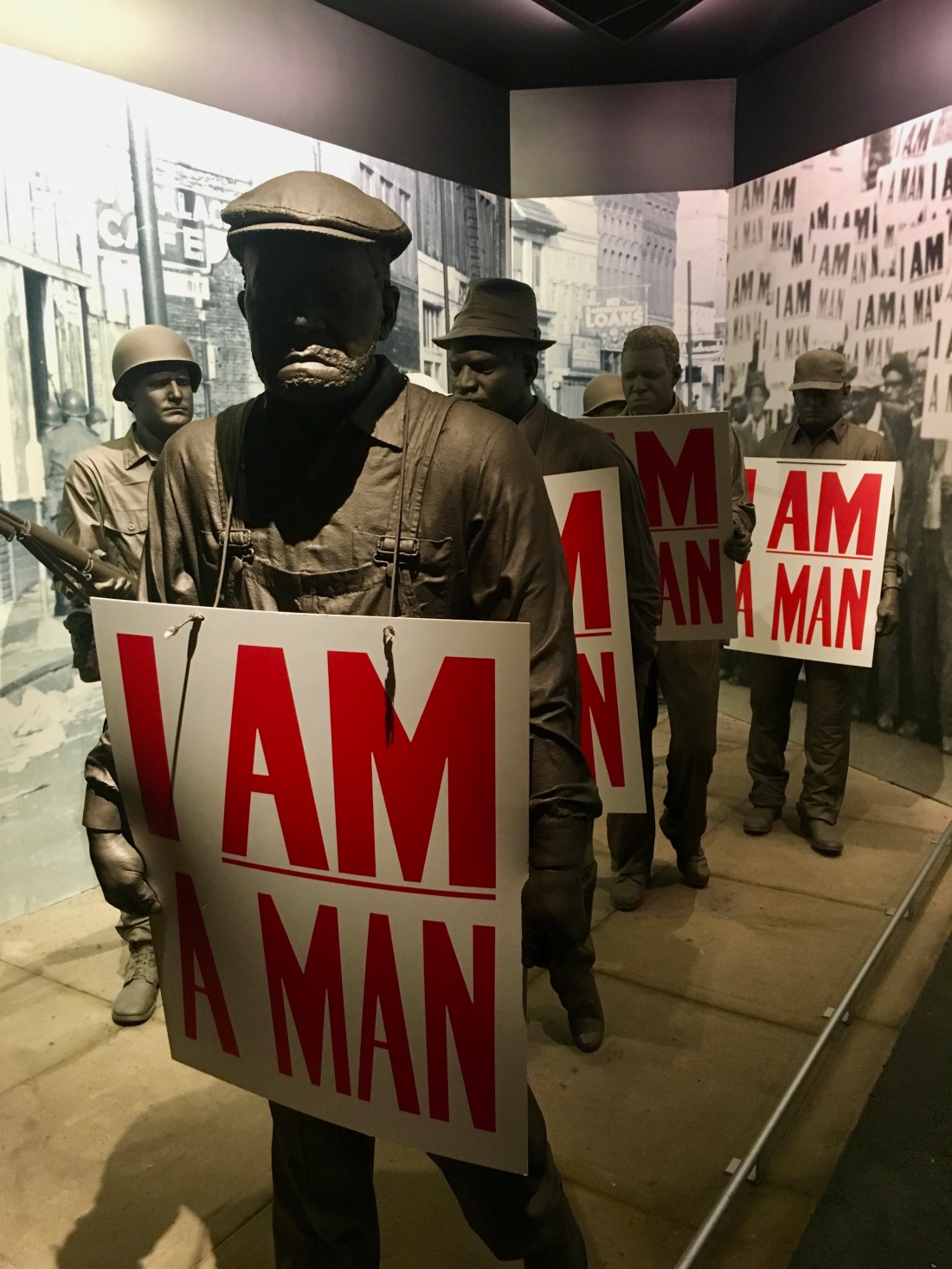

Memphis is the site of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King. He was infamously shot while standing outside his room at the Lorraine Motel in 1968. Part of the motel still stands, now transformed into the National Civil Rights Museum. The museum does an excellent job of educating, with stirring displays covering topics from slavery, to civil rights, and includes current day issues. At the end you can walk upstairs and look inside the room where the Reverend took some of his last breaths.

Another heart-rending moment was one of the first rooms in this museum, which demonstrated the scope of the transatlantic slave trade. Millions of Africans were stolen from their homeland, kept in deplorable conditions, many dying en route, while auction and a life of slavery awaited those who survived the horrendous journey. I remember a drawing (like the one below) reading firsthand accounts of experiences on the ships, and having difficulty fathoming how people could be so barbaric. I had the grievous thought that even if the slave traders ignorantly viewed blacks as inferior people, these conditions weren’t even fit for animals.

Over MLK weekend, Jeff and I went with several members of The Memphis chapter of Be The Bridge (a national Christian community with a goal of encouraging healthy dialogue around racial topics and working towards racial unity) to Alabama to visit several museums and historical sites. The first stop on the trip was the recently opened Legacy Museum: from Enslavement to Mass Incarceration in Montgomery.

Montgomery, with easy access to the Alabama River and railroad routes, played a key role in the domestic slave trade. Just a few blocks from the river dock, the Legacy Museum was built on the site of a warehouse where blacks were imprisoned and trafficked during that period. We had to go through security to enter the museum, and then they did not allow any video/photography. (Side note: Why is it that the Civil Rights Museums we visited of late and the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC have airport-level security to enter while most other museums I’ve visited do not?)

Before entering the large, open room where most of the museum was housed, we were funneled through a dark passageway with cells to simulate the confines the slaves had to endure. We could look behind the bars, see holograms of individuals in shackles, and hear their stories. Parents were distraught over being separated from their children. Children were begging to see their parents. Others were consoling themselves with spiritual songs. Bodies, faces, and voices given to the souls that were terrorized in this building.

After this haunting yet poignant preface, we entered the main section of the museum where we were overwhelmed with displays, timelines, quotes, videos, and interactive experiences to teach us more about racial injustice in our country. This museum, along with the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which I will discuss more later, were started by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) which, “is a private, nonprofit organization that challenges poverty and racial injustice, advocates for equal treatment in the criminal justice system, and creates hope for marginalized communities.” EJI was founded by Brian Stevenson, a public interest lawyer, and author of the acclaimed book, Just Mercy. I mention these because they are excellent resources that I encourage you to look up to understand more about our history and the ongoing issues we face.

Now is the part where I may begin to intermix the information I learned from various experiences and try to convey some of my take-aways…

The North won the Civil War and slavery was abolished via the 13th amendment, hooray! Well, that’s what I was taught in school but I don’t recall discussing the verbiage that still (yes, even to this day) allows slavery as punishment for a crime. So what happened in the South after the ‘abolition of slavery’? Convict leasing. Essentially continued bondage for mostly black men who received discriminatory sentences for crimes they often didn’t commit. They were then leased to private parties such as plantation owners and continued to be exploited for labor.

Another way of reinforcing the mindset of slavery by inciting fear and continued subjugation: racial lynchings. Before this educational trip, I thought of lynchings more as isolated events organized by radical groups such as the KKK. I didn’t understand it as the domestic terrorism that it was.

Many of the killings occurred in broad daylight under the complicit watch of government officials and law enforcement. For example, Ell Persons was lynched in 1917 in the county I currently live in here in Memphis, in front of a crowd of 5,000 spectators. Jesse Washington was killed the previous year in Texas in front of 10,000 spectators. These grotesque murders provided carnival-like atmospheres for the white observers, while instilling fear and horror in the black community.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is the first of its kind in our country. It memorializes the victims of lynching crimes as well as shedding light on the topic. It is one of the most powerful, moving memorials I have experienced. Sculpture blocks each representing a county in which these hate crimes occurred hang at a single level from the ceiling. The interpretive walkway gradually descends beneath to provide varying perspectives and appropriate scope to the subject. Each block is engraved with names, as well as dates, of the lynching victims. An identical block lies outside the main structure in hopes that the county in which the crimes occurred will reclaim it and display it as a way of confronting its past.

Along one of its walls, the memorial recorded explanations given for some of the lynchings. While some involved serious accusations, many were trivial or even noble acts. African Americans were killed for conduct or allegations such as disrespecting the wrong person or group of people, refusing to turn in a family member to authorities, or simply being a leader or organizer in the black community.

Another clear take-away from delving deeper into our nation’s history of civil rights issues is that the law often changes before the popular mindset. Just because a law desegregated schools, or allowed everyone the right to vote, did not mean that these things were implemented smoothly nor universally.

At the Legacy Museum I read a prominent quote uttered by George Wallace, governor of Alabama during his inauguration speech in 1963 that ended with the exclamation: “I say segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever!” As I was contemplating these words, I heard the gentleman besides me quietly say, “I remember when he said that.” At that point it really struck me, we are hardly a generation removed from this shameless mindset. Do we think the children of the George Wallaces out there think significantly differently? What about the grandchildren? How many generations does it take and what other changes are needed to take place to foster an attitude of true equality?

Another fact that put this timeframe in perspective is that interracial marriage laws were not universally abolished until 1967! That was not too long after my parents were born. Had they been born a decade earlier and lived in a different state, they would have been legally forbidden from marrying. Heck, if I was born in a not-too-distant era, I could have been banned from marrying my husband as well.

Finally, on to our criminal justice system. I knew there was racial bias in this area but didn’t realize just how blatant it was. According to the EJI, African American males are 6 times more likely to be sentenced to prison for the same crime as a white person, and currently 1 in 3 African American males will spend some time in prison during his lifetime.

Is this purely socioeconomic? Our legal system certainly favors the wealthy, with those living in poverty having difficulty paying fees and securing good legal representation. But there is also a disproportionate rate of arrest and conviction among African Americans compared to their white counterparts and often a presumption of guilt.

One thing that I hadn’t really thought about was how laws could be written, or certain offenses could be treated more harshly in an attempt to silence specific groups of people. For example, Nixon’s aide John Ehrlichman later admitted that the administration’s “War on drugs” and movement to criminalize drugs was politically motivated to disrupt black communities (and liberal leaning hippies) rather than for fear of drugs themselves. Wow.

There are a host of other issues that I’m nowhere near qualified to discuss: prosecution of minors, unreliable convictions, excessive punishments, poor prison conditions and reintegration programs, felons’ rights and treatment upon release to name a few. Again, EJI (eji.org) has some excellent resources in these areas.

In general, it’s probably prudent to reflect on our justice system and the intent of certain tough-on-crime policies. What groups of people do these laws help versus hurt? Can they be and are they equally enforced? Do they work towards long-term rehabilitation and building safer communities or do they foster more fear and segregation? Are there models from other countries that we could learn from? (In 2015 the U.S. had 21% of the world’s incarcerated population despite having only 4.4% of the world’s total population.)

I know that reflecting on some of these issues can open a Pandora’s box of other issues. But these things are important to think about and be aware of, even if they don’t lead to easy or obvious answers. The more I learn, the more I realize how complex these issues are and how intertwined they are with past and present political, cultural, and idealogical biases.

Memphis, and most other major U.S. cities, remain largely segregated along racial and ethnic lines. Memphis is over 50% black but I would not know that by the commercial areas that I frequent nor, sadly, the church that I attend. There are ongoing disputes over school district lines and zoning divisions that I presume have socioeconomic and racial underpinnings. Many amazing people and organizations here are working towards a better understanding of these issues and racial reconciliation, but there is still a long way to go.

So what are we going to do about it? Well, first we have to admit it’s a problem, if we’re in denial about that, then it’s hard to move forward. Second, we can continue to learn more about issues in our community and at the national level in order to become a more informed voter, find organizations to get involved with or donate our resources to. Remember that change requires more than just knowledge and words but action.

That said, the foundation for positive change is undoubtedly our underlying attitude. We must be willing to have compassionate and constructive conversations about these issues. Dr. Martin Luther King is quoted as saying, “Men often hate each other because they fear each other; they fear each other because they don’t know each other; they don’t know each other because they don’t communicate.” It can be easy to buy into the simple narrative of fear and vilifying ‘the other’ whom we don’t really know or understand. It is harder to actually take that step towards genuine communication and seeking to understand someone else’s unique circumstances. We must approach these issues with humility and each examine ourselves: Are we content to continue to stand still while these issues remain or even worsen around us? Or are we prepared to take a step towards reconciliation?